When getting ready to have surgery, we are used to being briefed by our surgeon, the nursing staff, and the anesthesiologist as to what will take place during the operation and what to expect afterward. But, have you ever wondered what’s really going on with your body while you’re asleep under anesthesia?

Dr. Bryan Marascalchi, an assistant professor of anesthesiology and critical care medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, discussed the process quite expertly.

“[Anesthesia] is really kind of a mixture of different components,” Marascalchi said. “You have the lack of pain, the lack of motion, the lack of consciousness or awareness, and more.”

“We use different agents to augment those different parameters,” said Marascalchi. “So, for immediate surgical pain we give non-opioids adjuvants such as acetaminophen or NSAIDs as well as opioids – a medication that works on opioid receptors to reduce pain while you’re under anesthesia.”

Think about being under general anesthesia as being similar to being awake and falling off a bike or tripping off a curb. “It’s just like if you hurt yourself, you would have an increased heart rate or blood pressure,” said Marascalchi. “You would have the same thing due to surgical stimulation under anesthesia, and to prevent that we use pain relieving medications.”

After each surgery I’ve had, I didn’t recall anything about the procedure after being put under anesthesia. I assume most people have the same experience. The medications that prevent memory formation of the events that transpired while on the operating table are called amnestic agents.

Marascalchi said a common agent used is Midazolam. “That prevents memory from forming.”

When it comes to administering agents to lead the patient to lose consciousness, “which is a reduction in brain wave activity,” there are “agents like anesthetic gases – sevoflurane, isoflurane, desflurane; those are kind of the more popular ones, and then Propofol.”

The last part of anesthesia, Marascalchi explained, is “paralysis and we use paralytic drugs so when there’s a surgical stimulus,” the patient doesn’t move.

When I mentioned to Marascalchi that I was given Propofol during my most recent surgery, he provided further clarification on the drug. “Propofol acts really quickly,” he said. “That’s why it’s given first.” He explained that while Propofol can be used as a sole anesthetic for certain non-painful procedures, or throughout a case in conjunction with other agents “often times it is used just to get you deep enough for intubation, and then we switch to the anesthesia gases.”

It was interesting to learn that Propofol puts a patient under within seconds, compared to having to breathe anesthesia gases to achieve the same result – not to mention their pungent odor.

And this is just the beginning stage of being put under!

The next phase is undoubtedly unpredictable, ever-changing, and warrants a keen eye by the anesthesiologist.

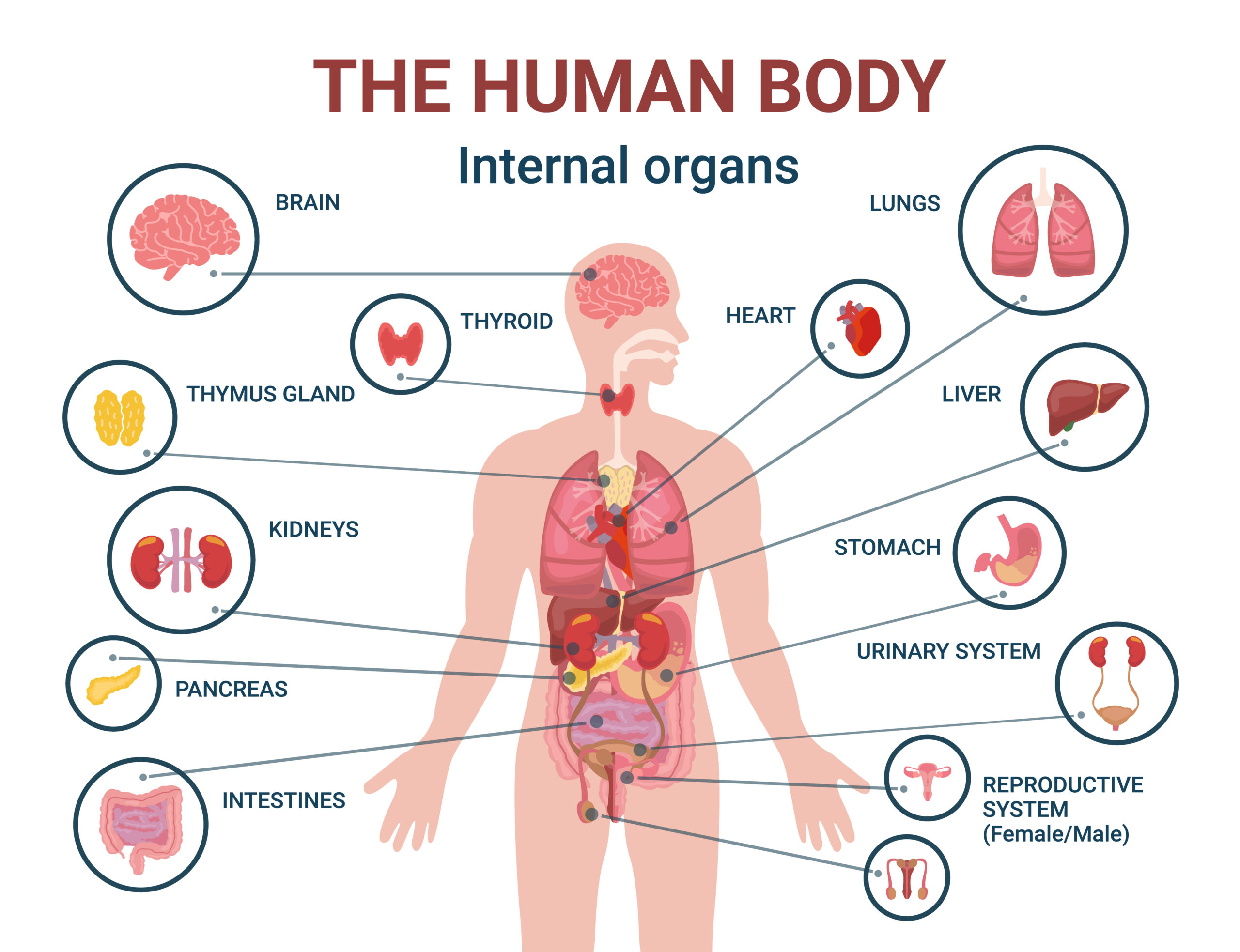

When asked what the primary things are that an anesthesiologist is closely monitoring when a patient is under, Marascalchi said, “All of the different organ systems could in theory be affected.”

I hadn’t yet considered how age could be a factor in anesthesia. Marascalchi dives into the topic and shares that while highly debatable, “We don’t really want children to have to go under anesthesia if they don’t have to. We believe that to protect the neurons, you don’t want to give them anesthetic drugs, especially during development.”

He said that if it’s an elective surgery, its ideal to wait until the child is over the age of 3 years.

This absolutely makes sense to me, but as we know sometimes it’s unavoidable due to early-life complications some infants experience.

When looking at the other end of the spectrum, older patients can experience delirium after being put under. Marascalchi explained, “If you’re older after you awaken from anesthesia you can be delirious known as post-operative delirium. So, it can affect cognition. In those with delirium at baseline the post-operative effects can be as long as 6 months.”

Those side effects and concerns are for those two age brackets, but for the general public, anesthesia “can also affect a lot of other organ systems.”

The experience begins when you lie on the operating table. Marascalchi said at that point an injury can occur. “How you’re positioned on the operating table is very important,” he said. “You have to make sure that everything’s padded and you’re well placed.”

As you can tell even at this early stage in your lead-up to an operation, there are endless things that need to be exact for the benefit of your health and recovery.

If Propofol is used, as an example, Marascalchi explained it is a drug that “very much lowers your blood pressure.”

It can also affect the function of the heart. “Heart rate can either go up to try to maintain the blood pressure or your heart rate can go down and both can be concerning,” he said. “Too much Propofol would be deadly. And that’s exactly why it’s a so carefully titrated drug.”

Marascalchi said, “Anesthetic gases do the same thing. For the most part they vasodilate, and that dilation reduces blood pressure and alters heart function and [the anesthesiologist has] to be able to react to that.”

How is a drastic rise or fall of a patient’s blood pressure treated? Is it by lowering the gases used or are medications commonly provided intravenously?

“A little bit of both,” Marascalchi said. “Basically, you can dial in the anesthetic gases, but that takes a little bit of time. If you have time – you can just wait.” The other solution is giving medications “that increases the vasoconstriction of the vessels, speeds up the heart rate, or improves the strength of the heart contractions – thus increases the blood pressure or there’s medications that do the exact opposite.”

“Beta blockers and other agents [can be administered] that decrease the heart rate and blood pressure,” he said. “So you can be in control of [treating a patient] through multiple different ways.”

Understanding a patient’s medical history is key for anesthesiologists. As we each have unique bodies, being fully transparent before surgery can only benefit you. This information includes any previous problems with major organs such as kidneys, liver, heart, etc.

Marascalchi said that most, if not all, organs can be affected by anesthesia. For example, “Certain drugs can affect the kidneys. There are certain drugs that are metabolized by the kidneys and should somebody have kidney issues you don’t want to give these medications to them.” This could result in a dangerous outcome.

The same goes for the liver – and such, people can have liver failure.

In addition, treating patients that are arriving on an emergency basis at the hospital presents another set of challenges. “For example, there can be drug – drug interactions, so you have to be careful of the drugs that can harm various organ systems, as well as individual variations, and pre-existing conditions,” Marascalchi explained.

“I almost think I could come up with an example of every organ system,” he said. “Anesthesia affects the cardiovascular system, central nervous system, gut, almost everything. Even the eyes can be affected, if you don’t close the eyes and protect them.”

I never knew that vision loss, stroke, kidney injury and more are linked to blood pressure, so “maintain[ing] the right blood pressures” of each patient is paramount.

And after all is said and done and you’re in the recovery room, many surgery patients experience that their bladders are slow to wake back up. Marascalchi clarified that, “anesthetic medications including opioids can cause urinary retention, where the bladder is unable to void urine and you retain urine.”

In addition, he said, “Opioids slow down the gut.” If you are a person that has experienced nausea post-surgery, Marascalchi said that, except Propofol, “many anesthetic agents including opioids and the anesthetic gases can cause the CTZ (chemoreceptor trigger zone – known as the ‘vomit center’ in the brain) to activate, causing nausea.”

The mysterious ways our bodies react to anesthesia is a little less of a mystery after learning so much from Dr. Marascalchi.

On top of that, it makes me (and hopefully each of you) want to say a huge thank you to the anesthesiologist treating us in surgery. Our lives are literally in their hands while they apply their in-depth knowledge, intuition, and take action to give us the best possible outcome from being on the operating table.

Dr. Bryan Marascalchi serves as an assistant professor of anesthesiology and critical care medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. In his pain management practice, he specializes in treating patients with persistent pain in the spine, complex regional pain syndrome, disc pain, sciatica, and neuropathic pain. Dr. Marascalchi is also an innovator in his field, having helped develop the Pneumico Ventel™ and the Pain Scored platform.

Watch for more from Dr. Marascalchi on January 27, 2022

Coming next: Failure can illuminate new paths

Please consider sharing this article with family, friends, neighbors, coworkers. Let’s help each other reach optimal health.