As you likely realize by this stage, bringing awareness and fostering conversation on overall health, especially chronic conditions is what drives me.

Many of these conditions cause patients to feel significant fatigue. In some cases, the fatigue is so profound that it is disabling and the individual can no longer perform everyday chores or the work they have depended on for their livelihood.

It was enlightening to interview Staci Stevens, founder of Workwell Foundation (“Workwell”). Workwell provides disability evaluations for individuals with fatigue-related illnesses. The foundation focuses on research concerning the functional aspects of ME/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome in order to facilitate an understanding of the biological basis for fatigue and post-exertional malaise (PEM). Bringing awareness and education to society is paramount in their mission.

Stevens explained that the all too common reality is that patients come to Workwell “when they are so stressed; when their disability is on the line.” Financial stressors aren’t the only motivating factor, one of the hardest or most discouraging parts.

“[These individuals] are really, really sick and people don’t believe them,” said Stevens, who explained that Workwell provides functional evaluations, not diagnoses.

People that do not experience chronic fatigue have a hard time understanding that it truly is a “real” condition. Bringing awareness of this is important. Many doctors have alluded to patients that it “must be in their head,” without searching further to see what underlying cause may be causing the patient such problems.

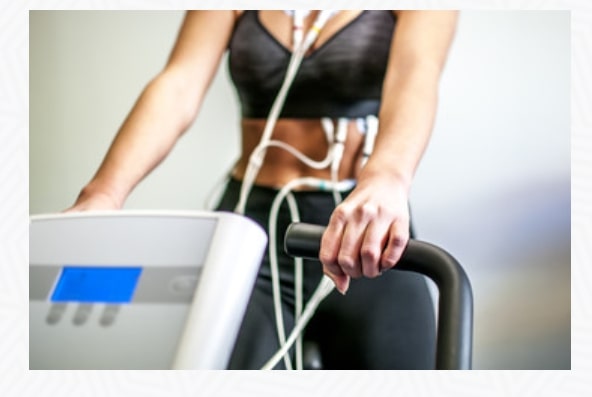

For those wondering what ME/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome does to the metabolic systems of patients, in the Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test (CPET), the oxygen analyzer “actually measures every breathe you breathe out, so [Workwell] is measuring expired air,” Stevens said.

“Room air is 21 percent oxygen, the oxygen analyzer producing what the person is breathing in/out, the difference is what [a patient] uses, and the pulsometer [placed] on the [patient’s] finger” allows Workwell to know the amount of oxygen available in the blood.

The outcome? Workwell is finding out that for ME/CFS patients “the oxygen is available; they just can’t use it, and so [they] are finding low peak aerobic capacity.” Most of us are aware that nobody functions at 100% capacity of aerobic capacity. That would be unsustainable. The functional level is “where you can sustain activity” and it’s that measurable point that Workwell is “able to attach an oxygen consumption or oxygen cost to the point,” Stevens explained.

For a majority of ME/CFS patients, “light [daily] activities are like running a sprint and running multiple sprints, and nobody can do 50 of those without cumulative fatigue and pain.”

Ultimately patients are “living their lives over that threshold” (i.e. shifting earlier to anaerobic metabolism). For all means and purposes “light daily activities” is defined as getting dressed, taking a shower, and emptying the dishwasher, to name just a few.

Compare these activities and symptoms with an individual who does not have a chronic condition such as ME/CFS. For a “healthy” person, exercise may feel challenging, perhaps causing perspiration, in which case exceeding the anaerobic threshold. But, the end result is “Wow, I feel good. I feel sore, but I feel energized.” ME/CFS patients on the other hand experience a flurry of symptoms, both immediately and spanning several days to a week or more.

According to Stevens, Fibromyalgia and ME/CFS “are very similar in that there is about a 70% overlap” between the two conditions. For all of Workwell’s purposes, the chronic illness a patient has is irrelevant. “What matters is – are they functionally impaired and what systems are problematic?” explained Stevens.

Post-exertional malaise (PEM) “is that defining feature and a lot of Fibromyalgia patients have that. What distinguishes the Fibromyalgia from ME/CFS often times is the pain overlay,” Stevens said. Widespread body pain is common for Fibromyalgia patients.

The two most important questions that can define PEM, Stevens said, are: 1) Do you have symptom flare-up after you overdo activities or exercise? (This can be emotional, physical, cognitive, sensory) and 2) Does it last longer than 24 hours?

“[If so,] patients are in this chronic inflammatory response that they can’t get out of,” she said. “PEM has immediate short term and long term symptomology that pairs with the path of physiology.”

In my life experience, “fatigue” is a relatively common expression of symptoms. In most cases, people are referring to a rather short-term experience. For example, hearing a colleague say, “I’m tired, it’s been a long week,” or an employee at a store say “I feel fatigued after 3 nights up with my sick baby.”

It’s important to note that short-term fatigue is a very different experience from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.

Stevens explained Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. “This isn’t just fatigue; patients will describe it as bone-crushing; they can’t move; they feel like they are in quicksand; it’s this heaviness, it’s system-wide.” She likened it to having the flu.

“And it’s just really managing the level of the flu,” she said. “And when you don’t manage it, the flu gets worse. And [the patients] just can’t function.”

“One of the hallmark symptoms of ME/CFS is patients never wake up feeling refreshed,” Stevens explained. “No matter how much they rest; it doesn’t resolve.”

Headache is one of the symptoms of PEM that appears in the two-to-four-day range. “The neurological system and cardiopulmonary system tend to be involved two-to-four-days later, and that’s where the headache, migraine, the sleep disturbances and the muscle and joint pain” start appearing as symptoms in a patient, Stevens noted.

The initial onset PEM symptoms after the CPET test include “being out of breath, nausea, dizziness, brain fog, fatigue,” said Stevens.

The goal for management of PEM is “identifying what is your first symptom of overdoing it, what is that first flare up, identify that and then stop and rest, lay down,” emphasized Stevens.

After performing the CPET, ME/CFS patients have 18 different symptom categories, and those categories “change and amplify,” Stevens said.

Studies completed by the National Institute of Health (NIH) and Workwell have concluded that half of the patients who undergo the CPET are recovering within 2 to 4 days. As with any medical test or procedure, it is important for the patient to weigh the pros and cons (risks vs. rewards, if you will), and always consult with their health care professional.

Stevens has offered this advice to all patients, “Listening to your body, listening to your symptoms is key. We encourage our patients to listen to their symptoms and respect them and respect their energy systems.”

Staci Stevens previously served on the Department of Health and Human Services Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Advisory Committee and as co-vice president of the International Association of ME/CFS. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Sports Medicine and a master’s degree in Exercise Physiology, both earned from the University of the Pacific.

Coming next: Never forget: Actions speak louder than words

Please consider sharing this article with family, friends, neighbors, coworkers. Let’s help each other reach optimal health.